- Self-defense for women in 1942

- For those of us doing revisions, even of the non-NaNo variety

- Lee Child on writing suspense

- File under things I don't know enough about: the War of 1812

Saturday, December 15, 2012

Links (short version)

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

Great Expectations, post the second

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Don't forget, Leila's got the full list of posts over at Bookshelves of Doom!

- Spoke too soon. The Gargery-Pirrip family will be going through the Christmas rituals after all.

- "So, we had our slices served out, as if we were two thousand troops on a forced march instead of a man and boy at home; and we took gulps of milk and water, with apologetic countenances, from a jug on the dresser."

- "Mrs. Joe was a very clean housekeeper, but had an exquisite art of making her cleanliness more uncomfortable and unacceptable than dirt itself."

- "I was always treated as if I had insisted on being born in opposition to the dictates of reason, religion, and morality, and against the dissuading arguments of my best friends."

- "I opened the door to the company,—making believe that it was a habit of ours to open that door,—and I opened it first to Mr. Wopsle, next to Mr. and Mrs. Hubble, and last of all to Uncle Pumblechook. N.B. I was not allowed to call him uncle, under the severest penalties."

- " the Pumblechookian elbow in my eye"

- If you've gotten this far into the book and are not feeling profoundly sorry for Joe Gargery, I'm not sure we're on speaking terms any more. That man needs a hug. And while I don't remember all the details from the last time I read the book, I'm fairly sure he's not going to get one.

- For the moment, things look bad for Pip, as it turns out he didn't water down the brandy to cover what he gave the convict, he poured the infamous tar-water into it.

- There's another reference to the fact that Pip is looking back and telling this story, and it's a curiously phrased one: "I moved the table, like a Medium of the present day, by the vigor of my unseen hold upon it." But I guess the paranormal stuff didn't really get started until the last third of century.

- This is one of the rare occasions in literature where the arrival of soldiers bearing handcuffs is actually a good thing. In a way.

Chapter 5

- For a character who never gets a name of his own, the sergeant is a rather clever bit on Dickens' part. He knows just what to say to everyone -- and manages to flirt with Mrs. Joe while keeping a straight face.

- Poor Joe. Everyone else gets to sit around and drink wine while he has to follow his Christmas dinner with a stint at the anvil.

- "I thought what terrible good sauce for a dinner my fugitive friend on the marshes was."

- I love that Pip now thinks of the man as "my particular convict."

- Curiouser and curiouser: When they catch the two convicts down at the marshes, Pip's convict makes a point of noting that he captured the other one. When the sergeant points out it's not likely to get him any time off, "'I don't expect it to do me any good. I don't want it to do me more good than it does now,' said my convict, with a greedy laugh. 'I took him. He knows it. That's enough for me.'"

- Clearly there's a history between these two men. Otherwise, wouldn't they put a little more effort into dealing with the fact that the soldiers have recaptured them?

- "It had been almost dark before, but now it seemed quite dark, and soon afterwards very dark."

- And Pip's convict is demonstrating his humanity here, claiming he stole the food Pip brought him. This chapter is really just a stroke of luck for Pip.

Chapter 6

- This is an excessively short chapter.

- Why Pip doesn't make a confession of his own: "The fear of losing Joe's confidence, and of thenceforth sitting in the chimney corner at night staring drearily at my forever lost companion and friend, tied up my tongue."

- And there's the theme, right there: "In a word, I was too cowardly to do what I knew to be right, as I had been too cowardly to avoid doing what I knew to be wrong. I had had no intercourse with the world at that time, and I imitated none of its many inhabitants who act in this manner. Quite an untaught genius, I made the discovery of the line of action for myself."

Don't forget, Leila's got the full list of posts over at Bookshelves of Doom!

Tuesday, November 20, 2012

Great Expectations, post the first

Leila is blogging Great Expectations. Which is awesome. (Follow her posts here.)

I haven't read it all the way through since high school.1 So let's see how far this attempt goes.

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

I haven't read it all the way through since high school.1 So let's see how far this attempt goes.

Chapter 1

- Dickens knew his openings: "My father's family name being Pirrip, and my Christian name Philip, my infant tongue could make of both names nothing longer or more explicit than Pip. So, I called myself Pip, and came to be called Pip." It doesn't make a lot of sense (or rather, parents who stick their kid with the name Philip Pirrip don't make sense, though they're certainly plausible), but the way he says it suggests there's more to it.

- It's always struck me as odd when adults in nineteenth-century fiction call each other by their married names, especially when they grew up together (e.g. "my sister Mrs. Norris), but Pip only thinking of his sister as Mrs. Joe? Totally makes sense.

- I am a sucker for marshes. Have I mentioned that before?

- Also skillful: first-person narration that keeps its distance from the narrator: "At such a time I found out for certain that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana wife of the above, were dead and buried; and that Alexander, Bartholomew, Abraham, Tobias, and Roger, infant children of the aforesaid, were also dead and buried; and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip"

- The convict? Utterly terrifying. And yet we're not very much in Pip's head here; we get lines like "I earnestly expressed my hope that he wouldn't."

- The w-for-v substitution in "wain" and "wittles" -- what dialect is that supposed to be?

- More great writing: "The marshes were just a long black horizontal line then, as I stopped to look after him; and the river was just another horizontal line, not nearly so broad nor yet so black; and the sky was just a row of long angry red lines and dense black lines intermixed."

Chapter 2

- Does Mrs. Joe have any redeeming qualities? We certainly don't find out about them when we first meet her.

- Of course, Joe has his merits, but Dickens isn't too kind to him either: "a sort of Hercules in strength, and also in weakness."

- "Tickler was a wax-ended piece of cane, worn smooth by collision with my tickled frame."

- Pip gets tucked into the chimney and then out onto a stool in a matter of sentences. There is clearly room for exploration here if you're turning this into a film.

- Mrs. Joe's bread-and-butter preparations? Oh, my. What a look into the household.

- Secreting one's bread in one's trouser leg is never a simple operation: "The effort of resolution necessary to the achievement of this purpose I found to be quite awful."

- "At the best of times, so much of this elixir was administered to me as a choice restorative, that I was conscious of going about, smelling like a new fence."

- It's Christmas Eve. And we're only just now finding this out. The Germans have definitely not made their impact on English traditions yet. (Because, after all, Pip is looking back to his youth, which must have been pre- or proto-Victorian.)

- "But she never was polite unless there was company."

- "from Mrs. Joe's thimble having played the tambourine upon it, to accompany her last words"

Chapter 3

- Does this remind anyone else of the troll in Harry Potter? "I had seen the damp lying on the outside of my little window, as if some goblin had been crying there all night, and using the window for a pocket-handkerchief."

- "One black ox, with a white cravat on,—who even had to my awakened conscience something of a clerical air"

- Pip's definitely identifying with the convict here. First the bread down his trousers reminds him of the leg irons, and now it's the way the cold attaches itself to his feet.

- "Something clicked in his throat as if he had works in him like a clock, and was going to strike."

Saturday, November 17, 2012

Reading break links

I'm halfway through Paul Shackel's Memory in Black and White, so I've put down the notebook for a few minutes so I can post some links instead:

- An excellent use of Photoshop

- Mr. Rogers in infographic form (side note: if your Facebook friends weren't among those reposting the picture of Mr. Rogers with Koko the gorilla, you don't have enough sentimental nerds in your life)

- Created land is poorly drained? Who would have thought?

- What Turing's Cathedral leaves out

- Digital humanities in action: making ancient documents legible

- Alexander McCall Smith on early female detectives

- Someday I'm going to write about why James Fallows is a brilliant writer, but for now just read for yourself

- I was totally hooked by Henry Wiencek's book teaser in Smithsonian, so the reviews (especially from my historian-hero Annette Gordon-Reed) are fascinating

- The reading skills journalists need

- An in-depth look at the first show I ever got hooked on

Sunday, November 4, 2012

Why I Vote

It sounds glib, but I'm voting because there is absolutely no reason not to.

- It's legal. Nothing stopping me there.

- I'm registered in Massachusetts. Even that was almost frictionless. I filled out a form at a table set up directly in front of my T stop on National Voter Registration Day, and a week or two later, my confirmation arrived in the mail.

- I have time. Polling stations here are open from 7 AM to 8 PM on Tuesday. (Yes, Tuesday. Apparently there are robocalls in the area suggesting otherwise. Nope.) I start work at 9 and get out of class by 6:30.

- I know who I'm going to vote for. None of that undecided business here. (And I care about the outcome of the two important races on the ticket.)

- My polling place is easy to get to. I walk down the street two blocks, turn the corner, and I'm there. (It is not, however, the closest I've ever lived to where I vote. When I lived in Wisconsin, I voted at the DMV branch directly across the street from my apartment. Wisconsin also had same-day registration, which was great.)

Wednesday, October 31, 2012

Need a writing prompt?

This guy works with robots, and he thinks that "at some point, we have to get over" emergency shutoff buttons.

Speaking of which: robot bees.

"I can tell you, it's strange to write a research proposal and have half your bibliography be science fiction."

Forget parrots, this beluga is trying to speak human.

A transcript of the Bretton Woods conference was just rediscovered.

Speaking of which: robot bees.

"I can tell you, it's strange to write a research proposal and have half your bibliography be science fiction."

Forget parrots, this beluga is trying to speak human.

A transcript of the Bretton Woods conference was just rediscovered.

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

All I have time for is links

- One of those times you can't improve on the headline: "Orca Mothers Coddle Adult Sons, Study Finds"

- On the other hand: boring headlines abound

- Apropos of the romance post: Eloisa James on her dual identity

- How Andrew Karre defines YA

- What we need more of: made-up nobility

- Go read David on spoilers

- Laptops and latent sexism

- A 1982 paean to computers in journalism

- The early days of CBS News

- Marketing diamonds (trust me, it's worth the read)

- Best amicus brief ever?

- Beatrix Potter's recipes (not for rabbit pie)

- I'm with Liz on social reading

- The problem with talking about "small business"

- Amateur scientists, totally new solar system configuration -- what's not to love?

- Digitized dresses to drool over at the Met

- Backlist-midlist conflict

Saturday, September 29, 2012

Bookstores and romance

1. A couple years back, I agitated for -- and then organized -- a romance-focused session

at Winter Institute. An RWA staffer and a couple booksellers from

member stores that offered decent romance sections told booksellers what

romance readers expect, and why they should care.

2. I’m a fan of romance without actually being a big reader of it. The truth is, I’m kind of a prude. Also, I’m a bitter single lady. We offer full disclosure here at Archimedes Forgets!

3. There have been versions of this post written every few months, with the same sort of arguments hashed out in the comments. And to be fair, I’m probably not saying anything new here either.

4. Don’t even get me started on the difficulty of trying to apply any sort of absolute to the independent bookstore sector. Which is not to say I haven’t done it before, because it’s human nature to look for the defining characteristics of a group.

5. What I feel reasonably confident in saying about indie booksellers as a class is that they don’t like being told what to do. I think that, even more than platitudes we throw around like “a passion for books,” is why people are willing to make sacrifices to run or work for small retail enterprises.

6. When I talk about independent bookstores, I mean the ones that sell entirely or primarily new books. I know next to nothing about the used book business.

7. Romance readers have, in general, been poorly served by many independent bookstores over the past decade. (Quite probably before that, too.) I’m not arguing with that premise. I’m not saying that romance readers should feel any sense of obligation to stores that don’t meet their needs.

8. We -- readers -- don’t make coldly practical economic decisions when it comes to books. If I’m talking about a clothing store that carries dresses outside my price range or below my size, I can be fairly dispassionate about it, but if a bookstore doesn’t carry the authors and genres I like -- especially if there’s an indication that they actively disdain them -- there’s more of a sense of judgment. Psychology people, have at it.

9. Booksellers are used to hearing complaints about their selection. Last week a customer told my coworker that he hated our store because we don’t carry computer books. A couple months back, a customer told me that she had stopped shopping with us because we carry too many new bestsellers and commercial fiction writers. It’s easy to accept that you can’t please everyone, but there are days when it feels like you can’t please anyone.

10. Shelf space is always a problem. Even stores that want to increase their romance (or whatever) inventory have trouble finding a place to stock it. Part of the problem is that bookcases are large pieces of furniture with fixed dimensions. It doesn’t help your picture book overflow if you’re able to free up half a shelf in memoir and one shelf in sports.

11. I don’t know what fraction of the book-browsing population notices, but cheap paper does not age well. The groundwood used in pretty much all mass-markets (along with an increasing number of trade paperbacks) turns yellow very quickly. If something’s been sitting on the shelves for a while, it shows.

12. There’s often a significant overlap between a store’s customers and its employees -- many booksellers started out as customers. So a store that isn’t drawing romance-reading customers is unlikely to acquire romance-reading employees unless they look elsewhere. (Thanks to Ann Kingman for pointing this out in the comments to a Booksquare post, ages and ages ago.)

13. Romance readers are well-served by e-books. Independent bookstores are not. This gap in interests may prove to be unbridgeable.

14. No store can be right for everybody. If you’re looking for an inexpensive book to read once and get rid of, a used bookstore is probably the best fit. This isn’t the “fault” of the independent bookstore selling new books at their cover price, it’s just another gap in interests.

15. There are, without question, a non-trivial number of book snobs working in independent bookstores. (And probably chain stores as well.) Some of these people have no compunctions about sharing their snobbery with the objects of it. Which sucks, because it’s very easy for a bad experience in a single store to color a customer’s feelings about independent bookstores in general. (Which brings us back to #5.)

16. For the record, I’m far from perfect, but I do try really hard not to display any judgment on people’s reading choices. (I wanted to say “not to pass judgment,” but who am I kidding? I judge based on footwear, hairstyle, and whether you understand the proper use of “literally.” I just try not to show it.) I’m no fan of Fifty Shades of Grey (see prudery reference above), but I’m not going to mock you for asking for it. Even if you’re the one saying derogatory things about it.

17. I don’t see any grand solution to the romance reader-independent bookstore divide. I’m not sure there is one. I think there are stores that could benefit from making themselves more amenable to the wants of romance fans, and I think there are stores for which it would be more trouble than it’s worth. And I know I can’t tell any store what to do with its inventory. But I can add my own whinging to the mix when I hear the same complaints again and again.

(Post format shamelessly cribbed from Chasing Ray. When La Colleen starts numbering her paragraphs, watch out.)

2. I’m a fan of romance without actually being a big reader of it. The truth is, I’m kind of a prude. Also, I’m a bitter single lady. We offer full disclosure here at Archimedes Forgets!

3. There have been versions of this post written every few months, with the same sort of arguments hashed out in the comments. And to be fair, I’m probably not saying anything new here either.

4. Don’t even get me started on the difficulty of trying to apply any sort of absolute to the independent bookstore sector. Which is not to say I haven’t done it before, because it’s human nature to look for the defining characteristics of a group.

5. What I feel reasonably confident in saying about indie booksellers as a class is that they don’t like being told what to do. I think that, even more than platitudes we throw around like “a passion for books,” is why people are willing to make sacrifices to run or work for small retail enterprises.

6. When I talk about independent bookstores, I mean the ones that sell entirely or primarily new books. I know next to nothing about the used book business.

7. Romance readers have, in general, been poorly served by many independent bookstores over the past decade. (Quite probably before that, too.) I’m not arguing with that premise. I’m not saying that romance readers should feel any sense of obligation to stores that don’t meet their needs.

8. We -- readers -- don’t make coldly practical economic decisions when it comes to books. If I’m talking about a clothing store that carries dresses outside my price range or below my size, I can be fairly dispassionate about it, but if a bookstore doesn’t carry the authors and genres I like -- especially if there’s an indication that they actively disdain them -- there’s more of a sense of judgment. Psychology people, have at it.

9. Booksellers are used to hearing complaints about their selection. Last week a customer told my coworker that he hated our store because we don’t carry computer books. A couple months back, a customer told me that she had stopped shopping with us because we carry too many new bestsellers and commercial fiction writers. It’s easy to accept that you can’t please everyone, but there are days when it feels like you can’t please anyone.

10. Shelf space is always a problem. Even stores that want to increase their romance (or whatever) inventory have trouble finding a place to stock it. Part of the problem is that bookcases are large pieces of furniture with fixed dimensions. It doesn’t help your picture book overflow if you’re able to free up half a shelf in memoir and one shelf in sports.

11. I don’t know what fraction of the book-browsing population notices, but cheap paper does not age well. The groundwood used in pretty much all mass-markets (along with an increasing number of trade paperbacks) turns yellow very quickly. If something’s been sitting on the shelves for a while, it shows.

12. There’s often a significant overlap between a store’s customers and its employees -- many booksellers started out as customers. So a store that isn’t drawing romance-reading customers is unlikely to acquire romance-reading employees unless they look elsewhere. (Thanks to Ann Kingman for pointing this out in the comments to a Booksquare post, ages and ages ago.)

13. Romance readers are well-served by e-books. Independent bookstores are not. This gap in interests may prove to be unbridgeable.

14. No store can be right for everybody. If you’re looking for an inexpensive book to read once and get rid of, a used bookstore is probably the best fit. This isn’t the “fault” of the independent bookstore selling new books at their cover price, it’s just another gap in interests.

15. There are, without question, a non-trivial number of book snobs working in independent bookstores. (And probably chain stores as well.) Some of these people have no compunctions about sharing their snobbery with the objects of it. Which sucks, because it’s very easy for a bad experience in a single store to color a customer’s feelings about independent bookstores in general. (Which brings us back to #5.)

16. For the record, I’m far from perfect, but I do try really hard not to display any judgment on people’s reading choices. (I wanted to say “not to pass judgment,” but who am I kidding? I judge based on footwear, hairstyle, and whether you understand the proper use of “literally.” I just try not to show it.) I’m no fan of Fifty Shades of Grey (see prudery reference above), but I’m not going to mock you for asking for it. Even if you’re the one saying derogatory things about it.

17. I don’t see any grand solution to the romance reader-independent bookstore divide. I’m not sure there is one. I think there are stores that could benefit from making themselves more amenable to the wants of romance fans, and I think there are stores for which it would be more trouble than it’s worth. And I know I can’t tell any store what to do with its inventory. But I can add my own whinging to the mix when I hear the same complaints again and again.

(Post format shamelessly cribbed from Chasing Ray. When La Colleen starts numbering her paragraphs, watch out.)

Friday, September 7, 2012

This week's links

- A book on women in early Hollywood? Yes, please.

- More problems with cities below sea level: when saltwater enters the aquifers.

- How-to-manage-women manuals that are really more about dealing with all employees.

- Was the Gloucester sea serpent just a whale in a fishing net?

- I don't completely agree with David's anti-sticker-book rant, but I do admire his passion.

Tuesday, September 4, 2012

The Adventure of the Reigate Squire

Also known, in the Project Gutenberg edition, as "The Reigate Puzzle."

Sherlock Holmes has definitely not made it into popular memory as a fragile man, but that's almost the image Watson paints in the opening paragraph:

Besides the Conan Doyle's ongoing "everything you see here is real" conceit, with all the dashed-out names and "oh, I couldn't possibly tell you but I know you'd recognize the reference if I did" moments, these digressions from the narrator make the Holmes universe that much bigger. It's not just fifty-some little stories, it's so many adventures Watson couldn't possibly manage to write them all down, even if he were allowed to.

Anyway. On April 14, 1887 (Watson specifies), Holmes is suffering from "nervous prostration" after the conclusion of a particularly grueling case. It takes some cajoling, but Watson manages to drag him off to a friend's country house.

Tell me, does this sound like the kind of houseguest you want?

You can just hear the long-sufferingness in Watson's narration when Holmes inevitably gets involved in the case:

Of note: Holmes' experiences with the police have resulted in an amusingly low level of expectations of their competence:

And a lesson: Whenever Watson thinks that Holmes is losing his touch, you can be pretty sure a major clue has just been unearthed. This story's example:

Sherlock Holmes has definitely not made it into popular memory as a fragile man, but that's almost the image Watson paints in the opening paragraph:

"It was some time before the health of my friend Mr. Sherlock Holmes recovered from the strain caused by his immense exertions in the spring of '87."But of course Watson can't actually tell us what those exertions were, because they're "too intimately concerned with politics and finance to be fitting subjects for this series of sketches."

Besides the Conan Doyle's ongoing "everything you see here is real" conceit, with all the dashed-out names and "oh, I couldn't possibly tell you but I know you'd recognize the reference if I did" moments, these digressions from the narrator make the Holmes universe that much bigger. It's not just fifty-some little stories, it's so many adventures Watson couldn't possibly manage to write them all down, even if he were allowed to.

Anyway. On April 14, 1887 (Watson specifies), Holmes is suffering from "nervous prostration" after the conclusion of a particularly grueling case. It takes some cajoling, but Watson manages to drag him off to a friend's country house.

Tell me, does this sound like the kind of houseguest you want?

"A little diplomacy was needed, but when Holmes understood that the establishment was a bachelor one, and that he would be allowed the fullest freedom, he fell in with my plans"After he's had some time to mope around, Holmes perks up when he hears that there's been a burglary in the area, with unusual results:

"The thieves ransacked the library and got very little for their pains. The whole place was turned upside down, drawers burst open, and presses ransacked, with the result that an odd volume of Pope's 'Homer,' two plated candlesticks, an ivory letter-weight, a small oak barometer, and a ball of twine are all that have vanished."Which gives us a chance to watch our two protagonists in opposition. Holmes, as always, zeroes in on an oddity that makes perfect sense to him, while Watson has no idea what he's talking about and dismisses the whole thing -- in this case, by reminding Holmes that detecting isn't much help in a rest cure.

You can just hear the long-sufferingness in Watson's narration when Holmes inevitably gets involved in the case:

"It was destined, however, that all my professional caution should be wasted, for next morning the problem obtruded itself upon us in such a way that it was impossible to ignore it, and our country visit took a turn which neither of us could have anticipated."The burglars, it turns out, have now taken in a second estate, adding murder to their rap sheet. And it just happens that the two targeted houses happen to belong to landowners with a persistent grudge between them.

Of note: Holmes' experiences with the police have resulted in an amusingly low level of expectations of their competence:

"I have made inquiries," said the Inspector. "William received a letter by the afternoon post yesterday. The envelope was destroyed by him."Recourse to Google: Watson observes that the house "bears the date of Malplaquet upon the lintel of the door." For those of us who lack his grounding in English history, that would be the 1709 Battle of Malplaquet, part of the Wars of Spanish Succession.

"Excellent!" cried Holmes, clapping the Inspector on the back. "You've seen the postman. It is a pleasure to work with you..."

And a lesson: Whenever Watson thinks that Holmes is losing his touch, you can be pretty sure a major clue has just been unearthed. This story's example:

"I was pained at the mistake, for I knew how keenly Holmes would feel any slip of the kind. It was his specialty to be accurate as to fact, but his recent illness had shaken him, and this one little incident was enough to show me that he was still far from being himself. He was obviously embarrassed for an instant, while the Inspector raised his eyebrows, and Alec Cunningham burst into a laugh. The old gentleman corrected the mistake, however, and handed the paper back to Holmes."Also, this week in the insights of Sherlock Holmes:

"It is of the highest importance in the art of detection to be able to recognize, out of a number of facts, which are incidental and which vital. Otherwise your energy and attention must be dissipated instead of being concentrated."

Friday, August 24, 2012

Meet Stompy (and other links)

- Apparently Boston's getting a new robotic neighbor

- Mars exploration family portrait

- "Would you ever ask a man that question?"

- Elephants communicate with infrasounds

- Rosalind Franklin's sister has written a book

- The Times presents backyard animals

- Go check out the beginning of the lovely Gwenda's new book!

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Holmes Project: The Adventure of the Dancing Men

This time we're opening with a bit of authorial soliloquizing on Watson's part:

By the time his little game is over, the latest client has arrived, a Mr. Hilton Cubbitt, "a tall, ruddy, clean-shaven gentleman, whose clear eyes and florid cheeks told of a life led far from the fogs of Baker Street."

Holmes sets up the framing this time: "You gave me a few particulars in your letter, Mr. Hilton Cubitt, but I should be very much obliged if you would kindly go over it all again for the benefit of my friend, Dr. Watson." And so Cubbitt gets to tell his own story, although he begins by denigrating his own narrative abilities. Always fake confidence, Hilton. It's the secret of success.

But actually, he starts off by giving us a clue. It doesn't seem that way at first, just an example of the traditional emphasis on family connections, but in this case it turns out to matter.

The actual mystery here is of less interest to me than the sociological aspect. Short version, Holmes cracks a murder case by solving a substitution cipher that involves the dancing men of the title -- not too difficult for someone who's written "a trifling monograph upon the subject."

"Holmes had been seated for some hours in silence with his long, thin back curved over a chemical vessel in which he was brewing a particularly malodorous product. His head was sunk upon his breast, and he looked from my point of view like a strange, lank bird, with dull gray plumage and a black top-knot."And then the strange, lank bird proceeds to explain to Watson how it's totally obvious he's not going to be investing in South African securities -- which, by the way, seem to be a favorite choice of Conan Doyle's investment-minded characters.

By the time his little game is over, the latest client has arrived, a Mr. Hilton Cubbitt, "a tall, ruddy, clean-shaven gentleman, whose clear eyes and florid cheeks told of a life led far from the fogs of Baker Street."

Holmes sets up the framing this time: "You gave me a few particulars in your letter, Mr. Hilton Cubitt, but I should be very much obliged if you would kindly go over it all again for the benefit of my friend, Dr. Watson." And so Cubbitt gets to tell his own story, although he begins by denigrating his own narrative abilities. Always fake confidence, Hilton. It's the secret of success.

But actually, he starts off by giving us a clue. It doesn't seem that way at first, just an example of the traditional emphasis on family connections, but in this case it turns out to matter.

"I'll begin at the time of my marriage last year, but I want to say first of all that, though I'm not a rich man, my people have been at Riding Thorpe for a matter of five centuries, and there is no better known family in the County of Norfolk... You'll think it very mad, Mr. Holmes, that a man of a good old family should marry a wife in this fashion, knowing nothing of her past or of her people, but if you saw her and knew her, it would help you to understand."Just in case you don't understand straight off that one of the themes of the story is the value of maintaining family pride -- and Englishness -- Conan Doyle keeps hammering the point.

"He was a fine creature, this man of the old English soil—simple, straight, and gentle, with his great, earnest blue eyes and broad, comely face. His love for his wife and his trust in her shone in his features."Also of note: Mrs. Hudson makes an appearance here only in a most indirect fashion:

"She has spoken about my old family, and our reputation in the county, and our pride in our unsullied honour"

"Dear, dear, one of the oldest families in the county of Norfolk, and one of the most honoured."

"Ah! here is our expected cablegram. One moment, Mrs. Hudson, there may be an answer."We're back in the Austen zone of servants who spend most of the story invisible.

The actual mystery here is of less interest to me than the sociological aspect. Short version, Holmes cracks a murder case by solving a substitution cipher that involves the dancing men of the title -- not too difficult for someone who's written "a trifling monograph upon the subject."

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

Holmes Project: The Adventure of the Norwood Builder

Holmes gets to speak first in this story. What does he do with his opener? He bemoans the lack of criminal masterminds since he got rid of Moriarty.

Before the substance begins, Watson tosses in another reminder that in this version of London, all the stuff that he writes about really happened:

To which Holmes replies with both a put-down and a demonstration of his own abilities: "You mentioned your name, as if I should recognize it, but I assure you that, beyond the obvious facts that you are a bachelor, a solicitor, a Freemason, and an asthmatic, I know nothing whatever about you."

You can't beat the English when it comes to putting a person in his place.

What Holmes' itinerary doesn't include is that McFarlane is also accused of murder, which is of course the bit that appeals here: "This is really most grati-- most interesting."

Conan Doyle chooses the form of a newspaper article to convey the salient details, but McFarlane is the one reading the paper aloud, so in a way he's telling his own story, in headline format. Watson gets to read the actual text of the article. It's very long, so here's the short version: Jonas Oldacre is missing, presumed dead, and McFarlane, his last known visitor, is the leading suspect.

Inspector Lestrade arrives before we return to McFarlane's story, this time in his own words. Because there's one other crucial detail here: Oldacre hired McFarlane, out of the blue, to prepare a will in which he leaves all his possessions to McFarlane, despite the fact that they had never met.

Lestrade is ready to wrap up the case right there, but Holmes delivers another verbal smackdown:

Holmes dashes out for a spot of investigating, and though he isn't pleased by anything he's turned up, we do learn that McFarlane's mother was once engaged to Oldacre, but gave up on him when she realized that cruelty to animals was not an attribute she wanted in a husband.

Also, we get this gem of a description of Oldacre's close-mouthed housekeeper: "But she was as close as wax."

In conveying the housekeeper's words through Holmes' retelling of his investigations, Conan Doyle turns to a technique called free indirect speech. (Hat tip to David Shapard and his annotated Jane Austen series for introducing me to the term.) Holmes doesn't quote the housekeeper directly, but he essentially repeats her words, shifted from first person to third person:

And then, in the closing paragraph, Holmes gets one more chance to remind us that he's going to be a character in a story someday: "By the way, what was it you put into the wood-pile besides your old trousers? A dead dog, or rabbits, or what? You won't tell? Dear me, how very unkind of you! Well, well, I daresay that a couple of rabbits would account both for the blood and for the charred ashes. If ever you write an account, Watson, you can make rabbits serve your turn."

If? Hah.

"With that man in the field, one's morning paper presented infinite possibilities. Often it was only the smallest trace, Watson, the faintest indication, and yet it was enough to tell me that the great malignant brain was there, as the gentlest tremors of the edges of the web remind one of the foul spider which lurks in the centre. Petty thefts, wanton assaults, purposeless outrage—to the man who held the clue all could be worked into one connected whole. To the scientific student of the higher criminal world, no capital in Europe offered the advantages which London then possessed."When he puts it like that, he's almost got a point, you know?

Before the substance begins, Watson tosses in another reminder that in this version of London, all the stuff that he writes about really happened:

"His cold and proud nature was always averse, however, from anything in the shape of public applause, and he bound me in the most stringent terms to say no further word of himself, his methods, or his successes—a prohibition which, as I have explained, has only now been removed."And then the client arrives, introducing himself as "the very unhappy John Hector McFarlane."

To which Holmes replies with both a put-down and a demonstration of his own abilities: "You mentioned your name, as if I should recognize it, but I assure you that, beyond the obvious facts that you are a bachelor, a solicitor, a Freemason, and an asthmatic, I know nothing whatever about you."

You can't beat the English when it comes to putting a person in his place.

What Holmes' itinerary doesn't include is that McFarlane is also accused of murder, which is of course the bit that appeals here: "This is really most grati-- most interesting."

Conan Doyle chooses the form of a newspaper article to convey the salient details, but McFarlane is the one reading the paper aloud, so in a way he's telling his own story, in headline format. Watson gets to read the actual text of the article. It's very long, so here's the short version: Jonas Oldacre is missing, presumed dead, and McFarlane, his last known visitor, is the leading suspect.

Inspector Lestrade arrives before we return to McFarlane's story, this time in his own words. Because there's one other crucial detail here: Oldacre hired McFarlane, out of the blue, to prepare a will in which he leaves all his possessions to McFarlane, despite the fact that they had never met.

Lestrade is ready to wrap up the case right there, but Holmes delivers another verbal smackdown:

"'It strikes me, my good Lestrade, as being just a trifle too obvious,' said Holmes. 'You do not add imagination to your other great qualities, but if you could for one moment put yourself in the place of this young man, would you choose the very night after the will had been made to commit your crime? Would it not seem dangerous to you to make so very close a relation between the two incidents? Again, would you choose an occasion when you are known to be in the house, when a servant has let you in? And, finally, would you take the great pains to conceal the body, and yet leave your own stick as a sign that you were the criminal? Confess, Lestrade, that all this is very unlikely.'"Lestrade, of course, has an answer for all of those points, even if it means leaving Occam's Razor on the shelf.

Holmes dashes out for a spot of investigating, and though he isn't pleased by anything he's turned up, we do learn that McFarlane's mother was once engaged to Oldacre, but gave up on him when she realized that cruelty to animals was not an attribute she wanted in a husband.

Also, we get this gem of a description of Oldacre's close-mouthed housekeeper: "But she was as close as wax."

In conveying the housekeeper's words through Holmes' retelling of his investigations, Conan Doyle turns to a technique called free indirect speech. (Hat tip to David Shapard and his annotated Jane Austen series for introducing me to the term.) Holmes doesn't quote the housekeeper directly, but he essentially repeats her words, shifted from first person to third person:

"Yes, she had let Mr. McFarlane in at half-past nine. She wished her hand had withered before she had done so. She had gone to bed at half-past ten. Her room was at the other end of the house, and she could hear nothing of what had passed. Mr. McFarlane had left his hat, and to the best of her belief his stick, in the hall. She had been awakened by the alarm of fire. Her poor, dear master had certainly been murdered. Had he any enemies? Well, every man had enemies, but Mr. Oldacre kept himself very much to himself, and only met people in the way of business. She had seen the buttons, and was sure that they belonged to the clothes which he had worn last night. The wood-pile was very dry, for it had not rained for a month. It burned like tinder, and by the time she reached the spot, nothing could be seen but flames. She and all the firemen smelled the burned flesh from inside it. She knew nothing of the papers, nor of Mr. Oldacre's private affairs. "Is it cheating to have your character reuse a technique that's worked for him in the past? Because that's what Conan Doyle does here, doing the same "pretend there's a fire and flush out what the criminal loves most" trick he pulled in "A Scandal in Bohemia," with the difference that in this case the flushed out object was the criminal himself, the not-murdered Jonas Oldacre.

And then, in the closing paragraph, Holmes gets one more chance to remind us that he's going to be a character in a story someday: "By the way, what was it you put into the wood-pile besides your old trousers? A dead dog, or rabbits, or what? You won't tell? Dear me, how very unkind of you! Well, well, I daresay that a couple of rabbits would account both for the blood and for the charred ashes. If ever you write an account, Watson, you can make rabbits serve your turn."

If? Hah.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Holmes Project: The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual

Conan Doyle allows Watson to open this story in a bit of a snit -- after all, to Watson, Holmes is not just the subject of well-received stories, he's a roommate, and one with more than a few irritating habits.

But the untidiness provides the framing for today's tale, because among the debris muddling up the Holmes-Watson household are piles and piles of notes from Sherlock Holmes' pre-Watson cases. When he realizes what they are, Watson is interested at once.

Except there's trouble. It's servant trouble, essentially, courtesy of a now-dismissed butler who had been flirting with the maids and snooping into the family papers, where he was reading up on "the singular old observance called the Musgrave Ritual." And then the butler disappeared. And a couple days later, so did one of the maids.

It takes Holmes about two seconds to figure out that the Musgrave Ritual is in fact a verbal map, and that the butler had figured it out and gone looking for whatever was hidden.

Holmes' conversation with Musgrave as they explore Hurlstone brings up an extremely fortunate coincidence: one of the trees given as an indicator in the Musgrave Ritual has been gone for years, but Musgrave just happens to remember its precise height, because back in the day his tutor made him practice trigonometry al fresco, by calculating heights all over the estate. Which is so creative I'm almost willing to give Conan Doyle a pass on his use of coincidence here.

And with a touch of trigonometry himself, Holmes manages to solve the Musgrave Ritual and locate the missing butler, rather too late to do the man any good, but he still pulls it off.

"although in his methods of thought he was the neatest and most methodical of mankind, and although also he affected a certain quiet primness of dress, he was none the less in his personal habits one of the most untidy men that ever drove a fellow-lodger to distraction""Untidy" in this case extends to a general disregard for furnishings, even if there is something almost noble about "proceed[ing] to adorn the opposite wall with a patriotic V. R. done in bullet-pocks."

But the untidiness provides the framing for today's tale, because among the debris muddling up the Holmes-Watson household are piles and piles of notes from Sherlock Holmes' pre-Watson cases. When he realizes what they are, Watson is interested at once.

"'These are the records of your early work, then?' I asked. 'I have often wished that I had notes of those cases.'"For Holmes, the inquiry is both an opportunity to brag about what he did "done prematurely before my biographer had come to glorify me," and also an excuse to delay the tidying even more. But mostly to show off.

"A collection of my trifling achievements would certainly be incomplete which contained no account of this very singular business."The business is brought to young Holmes by one of his university classmates, "a man of an exceedingly aristocratic type." There's a brief overview of his aristocratic connections, and then a line that's only significant when you know what follows:

"Something of his birth place seemed to cling to the man, and I never looked at his pale, keen face or the poise of his head without associating him with gray archways and mullioned windows and all the venerable wreckage of a feudal keep."Conan Doyle sets Reginald Musgrave up as one of the less objectionable varieties of English aristocrat -- sure, there's a touch of arrogance, but he's not ruining himself at the track or running with the Marlborough House set. He's been staying at home, keeping up the traditions of the Musgraves reaching back to antiquity: "I have of course had the Hurlstone estates to manage, and as I am member for my district as well, my life has been a busy one."

Except there's trouble. It's servant trouble, essentially, courtesy of a now-dismissed butler who had been flirting with the maids and snooping into the family papers, where he was reading up on "the singular old observance called the Musgrave Ritual." And then the butler disappeared. And a couple days later, so did one of the maids.

It takes Holmes about two seconds to figure out that the Musgrave Ritual is in fact a verbal map, and that the butler had figured it out and gone looking for whatever was hidden.

Holmes' conversation with Musgrave as they explore Hurlstone brings up an extremely fortunate coincidence: one of the trees given as an indicator in the Musgrave Ritual has been gone for years, but Musgrave just happens to remember its precise height, because back in the day his tutor made him practice trigonometry al fresco, by calculating heights all over the estate. Which is so creative I'm almost willing to give Conan Doyle a pass on his use of coincidence here.

And with a touch of trigonometry himself, Holmes manages to solve the Musgrave Ritual and locate the missing butler, rather too late to do the man any good, but he still pulls it off.

"'You know my methods in such cases, Watson. I put myself in the man's place and, having first gauged his intelligence, I try to imagine how I should myself have proceeded under the same circumstances."

Monday, August 20, 2012

A little learning is a good thing

Can we triangulate Elizabeth George Speare's take on education from her writing? It may just be possible.

As Exhibit A, we have Nat, the winning male in The Witch of Blackbird Pond's love triangle:

As Exhibit A, we have Nat, the winning male in The Witch of Blackbird Pond's love triangle:

"It's these Puritans," Kit sighed. "I'll never understand them. Why do they want life to be so solemn? I believe they actually enjoy it that way."Exhibit B stars Pierre, the loser in one of the two love triangles in Calico Captive:

Nat stretched flat on his back on the thatch. "If you ask me, it's all that schooling. It takes the fun out of life, being cooped up like that day after day. And the Latin they cram down your throat! Do you realize, Kit, that there are twenty-five different kinds of nouns alone in the Accidence? I couldn't stomach it.

"Mind you," he went on, "it's not that I don't favor an education. A boy has to learn his numbers, but the only proper use for them is to find your latitude with a cross-staff. Books, now, that's different. There's nothing like a book to keep you company on a long voyage."

Pierre bristled. "What do you take me for, a monk who spends his life with his head in a book? I told you, when I was ten years old my grandfather took me out of school to go into the trade. I can read well enough to tally up my year's accounts, never fear."What she's telling us, I suppose, is go to school but not too much, and don't you dare start dissing reading.

Friday, August 10, 2012

Holmes Project: The Adventure of the Stockbroker's Clerk

The phrasing used to open this story is not exactly familiar to a modern US reader. (Have not consulted with any Brits on this; anyone want to tell me if "connection" is still used in this context?)

Watson announces that shortly after his marriage, he "bought a connection in the Paddington district." The rest of the paragraph reveals that he's talking about a medical practice. Which is by way of distancing him from Holmes' detective work, right before Conan Doyle turns around and brings them back together.

They meet up, Holmes shows off a bit ("'I am afraid that I rather give myself away when I explain,' said he. 'Results without causes are much more impressive.'"), and he brings Watson along with him on a case.

The client of the moment is

This time Conan Doyle has Holmes have the client tell his story to Watson -- with a caveat that feels like an authorial wink:

"I'm not very good at telling a story, Dr. Watson, but it is like this with me"

(Incidentally, Pycroft? Was it really necessary to give a client a name just one letter different from Holmes' brother? Did Conan Doyle have as much trouble remembering which letter to type?)

Anyway. Pycroft is a stockbroker's clerk who was lured away from a respectable-enough new job with promises of a much bigger salary elsewhere. But elsewhere turned out to be rather sketchy, so he asked Holmes to look into things.

(Note: I am not inclined to include racial slurs here even when they're someone else's words. But I will say that Conan Doyle throws in an utterly gratuitous one here. And the context makes it worse. Go to the story, do a Ctrl + F for "with a touch of the", and you can see for yourself.)

Suffice it to say this wasn't one of my favorites.

Watson announces that shortly after his marriage, he "bought a connection in the Paddington district." The rest of the paragraph reveals that he's talking about a medical practice. Which is by way of distancing him from Holmes' detective work, right before Conan Doyle turns around and brings them back together.

They meet up, Holmes shows off a bit ("'I am afraid that I rather give myself away when I explain,' said he. 'Results without causes are much more impressive.'"), and he brings Watson along with him on a case.

The client of the moment is

"a smart young City man, of the class who have been labelled cockneys, but who give us our crack volunteer regiments and who turn out more fine athletes and sportsmen than any body of men in these islands"Let's pause a moment to look at the language here. First, look how the use of "but" sets up cockney as a pejorative term -- clearly Conan Doyle is not going for the "person born within earshot of Bow Bells" definition. And second, "these islands?" Ireland was solidly part of the Empire.

This time Conan Doyle has Holmes have the client tell his story to Watson -- with a caveat that feels like an authorial wink:

"I'm not very good at telling a story, Dr. Watson, but it is like this with me"

(Incidentally, Pycroft? Was it really necessary to give a client a name just one letter different from Holmes' brother? Did Conan Doyle have as much trouble remembering which letter to type?)

Anyway. Pycroft is a stockbroker's clerk who was lured away from a respectable-enough new job with promises of a much bigger salary elsewhere. But elsewhere turned out to be rather sketchy, so he asked Holmes to look into things.

(Note: I am not inclined to include racial slurs here even when they're someone else's words. But I will say that Conan Doyle throws in an utterly gratuitous one here. And the context makes it worse. Go to the story, do a Ctrl + F for "with a touch of the", and you can see for yourself.)

Suffice it to say this wasn't one of my favorites.

Wednesday, August 8, 2012

Holmes Project: The Adventure of the Yellow Face

This time, Conan Doyle starts us off with an author's note. (Or, I suppose, a narrator's note, since it's very much in Watson's voice.)

The client, Grant Munro, gets in a pretty good line before things get much further:

But gradually -- after a fair bit of nagging on Holmes' part -- he tells the story of the trouble with his wife, with what seems to me an overly-precise description of the financial aspects of his marriage.

So his wife's using money for something she won't tell him, and then strangers turn up in the neighborhood. And at least one of them sounds like something out of Buffy:

There's a nice long bit of Q & A without dialogue tags, which is always fun (and it is a long bit, so click through to read it; I'm not going to fill the page here), and Holmes sends Munro off with assurances that he'll stop by the next day.

Then he lays out his theory for Watson: the wife is hiding her first husband down the road from her current one. He admits that it's not conclusive, "But at least it covers all the facts."

The next day, we learn that it doesn't.

Hiding behind the mask is, in fact, a "coal-black negress," Mrs. Munro's child from her first marriage. This is the big secret she's been keeping from her husband, with about the weakest excuse a mother ever had for child abandonment. (Semi-abandonment. She left her daughter with a nurse in the US "because her health was weak." And then she made her wear a mask.)

Mrs. Munro spends some time trying to justify herself, or perhaps to elicit sympathy:

"[In publishing these short sketches based upon the numerous cases in which my companion's singular gifts have made us the listeners to, and eventually the actors in, some strange drama, it is only natural that I should dwell rather upon his successes than upon his failures. And this not so much for the sake of his reputation—for, indeed, it was when he was at his wits' end that his energy and his versatility were most admirable—but because where he failed it happened too often that no one else succeeded, and that the tale was left forever without a conclusion. Now and again, however, it chanced that even when he erred, the truth was still discovered. I have noted of some half-dozen cases of the kind; the Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual and that which I am about to recount are the two which present the strongest features of interest.]"With that framing device, we're set loose with Holmes and Watson experiencing a bit of nature, urban version, otherwise known as taking a walk. Watson goes to lengths to point out how unusual this whole exercise thing is for Holmes, but on one level, it's very much of a piece with their day-to-day life:

"For two hours we rambled about together, in silence for the most part, as befits two men who know each other intimately."And then of course a client enters the scene. He appears indirectly at first; he's been waiting for Holmes, gone off in frustration, and left his pipe behind. Holmes, of course, knows all manner of things about the man after a quick glance at the abandoned pipe. (Incidentally, when the man himself puts in an appearance, Watson notes that he's holding a "wide-awake" hat. For those who are as baffled by the term as I was, there are pictures.)

The client, Grant Munro, gets in a pretty good line before things get much further:

"It seems dreadful to discuss the conduct of one's wife with two men whom I have never seen before."Tell me, how did Oscar Wilde never steal that for an epigraph?

But gradually -- after a fair bit of nagging on Holmes' part -- he tells the story of the trouble with his wife, with what seems to me an overly-precise description of the financial aspects of his marriage.

"that she had a capital of about four thousand five hundred pounds, which had been so well invested by him that it returned an average of seven per cent"Naturally, the mystery involves what follows his wife's request for money, but Munro's close attention to sums never draws any particular scrutiny. That's a little surprising, since I'd though we'd reached the point in Anglo history when it became gauche to discuss money with mere acquaintances, but whatever.

"I have an income of seven or eight hundred"

"a nice eighty-pound-a-year villa at Norbury"

So his wife's using money for something she won't tell him, and then strangers turn up in the neighborhood. And at least one of them sounds like something out of Buffy:

"It was of a livid chalky white, and with something set and rigid about it which was shockingly unnatural."And then his wife sneaks out and lies about it. So let's recap the layers here. We've got:

- the wife's false story

- inside the husband's version of events

- inside the narrative as recounted by Watson

- inside the text written by Arthur Conan Doyle

There's a nice long bit of Q & A without dialogue tags, which is always fun (and it is a long bit, so click through to read it; I'm not going to fill the page here), and Holmes sends Munro off with assurances that he'll stop by the next day.

Then he lays out his theory for Watson: the wife is hiding her first husband down the road from her current one. He admits that it's not conclusive, "But at least it covers all the facts."

The next day, we learn that it doesn't.

Hiding behind the mask is, in fact, a "coal-black negress," Mrs. Munro's child from her first marriage. This is the big secret she's been keeping from her husband, with about the weakest excuse a mother ever had for child abandonment. (Semi-abandonment. She left her daughter with a nurse in the US "because her health was weak." And then she made her wear a mask.)

Mrs. Munro spends some time trying to justify herself, or perhaps to elicit sympathy:

"I had to choose between you, and in my weakness I turned away from my own little girl."And when her husband has a chance to process the fact that he's now a stepfather, Conan Doyle rewards him with another great line.

"I am not a very good man, Effie, but I think that I am a better one than you have given me credit for being."

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

Links for the week

A new take on the long-tail aspect of bookselling

There are mini Mini Coopers running around the Olympic fields

A multi-source "buy this book" widget

Coverage of the recent Keplers2020 event: from Ron Charles (1, 2, 3) and Peter Turner (1, 2)

It's Kidlitcon time again

Excuses, valid and otherwise, to watch animal cams

Background on the Olympics-related use of animated GIFs

There are mini Mini Coopers running around the Olympic fields

A multi-source "buy this book" widget

Coverage of the recent Keplers2020 event: from Ron Charles (1, 2, 3) and Peter Turner (1, 2)

It's Kidlitcon time again

Excuses, valid and otherwise, to watch animal cams

Background on the Olympics-related use of animated GIFs

Monday, August 6, 2012

Holmes Project: The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton

Conan Doyle opens this story with one of his efforts to make it look like this is something that really happened. To wit:

"Charles Augustus Milverton" is unusual in that there's not much of a mystery to solve here. It's more about Holmes' ethical system, and the crimes which he considers beyond the pale.

Holmes is not a fan of the title character, as he makes abundantly clear early on:

Milverton, it turns out, is "the king of all blackmailers," and the only reason Holmes is bothering to notice him at all is that he's been hired to recover some potentially embarrassing letters ("imprudent, Watson, nothing worse") on behalf of the woman who wrote them.

When the gentleman in question turns up at Baker Street, Watson gives the reader a rundown of his appearance, and it's not a flattering portrait:

So Holmes has failed in the negotiations he was hired for, but because he has such an antipathy against blackmailers, he's not giving up. Also, it's an excuse for him to trot out one of his disguises.

So Holmes and Watson set off to break into Milverton's safe, but they have to duck into hiding when it turns out Milverton's still up, waiting for an appointment. And then this is where things turn either sublime or absurd, depending on your response to lines like "'It is I,' she said, 'the woman whose life you have ruined.'"

This, of course, is the problem all blackmailers face, though most don't have Holmes and Watson watching from behind a curtain when they're shot by past victims. Holmes figures justice is being served, so he hangs back until the woman's done, burns all the letters in Milverton's safe, and skips off back to Baker Street.

And when the police come around the next morning to get his opinion on recent events, he's not all that inclined to help out:

But there's one minor mystery left to clear up in the story, and Holmes spends the last paragraph taking care of that one: Among the portraits of "professional beauties" in a photographer's window, he locates the one of the woman at Milverton's house. Her identity, of course, is never revealed.

"The reader will excuse me if I conceal the date or any other fact by which he might trace the actual occurrence."Duly noted, Dr. Watson.

"Charles Augustus Milverton" is unusual in that there's not much of a mystery to solve here. It's more about Holmes' ethical system, and the crimes which he considers beyond the pale.

Holmes is not a fan of the title character, as he makes abundantly clear early on:

"Do you feel a creeping, shrinking sensation, Watson, when you stand before the serpents in the Zoo, and see the slithering, gliding, venomous creatures, with their deadly eyes and wicked, flattened faces? Well, that's how Milverton impresses me."Yeah, ugh.

Milverton, it turns out, is "the king of all blackmailers," and the only reason Holmes is bothering to notice him at all is that he's been hired to recover some potentially embarrassing letters ("imprudent, Watson, nothing worse") on behalf of the woman who wrote them.

When the gentleman in question turns up at Baker Street, Watson gives the reader a rundown of his appearance, and it's not a flattering portrait:

"There was something of Mr. Pickwick's benevolence in his appearance, marred only by the insincerity of the fixed smile and by the hard glitter of those restless and penetrating eyes."He's pretty much a caricature of a villain, but let's overlook that a bit, because Conan Doyle gives him some rather good lines. Like this one, suggesting that the woman's friends come up with his ransom as a wedding present:

"this little bundle of letters would give more joy than all the candelabra and butter-dishes in London"This, of course, doesn't sit well with Holmes, who gives up on negotiations and tries to just take the letters back by force. Milverton points out that this is somewhat ineffective since he's not actually carrying the letters -- he has foresight, this one. And then he leaves.

So Holmes has failed in the negotiations he was hired for, but because he has such an antipathy against blackmailers, he's not giving up. Also, it's an excuse for him to trot out one of his disguises.

"Then, with the gesture of a man who has taken his decision, he sprang to his feet and passed into his bedroom. A little later a rakish young workman, with a goatee beard and a swagger, lit his clay pipe at the lamp before descending into the street."His plan, as it turns out, is to cajole the necessary information from Milverton's housemaid and then steal the letters from the safe. He's not concerned about things going wrong, but Watson is:

"As a flash of lightning in the night shows up in an instant every detail of a wild landscape, so at one glance I seemed to see every possible result of such an action -- the detection, the capture, the honored career ended in irreparable failure and disgrace, my friend himself lying at the mercy of the odious Milverton."But after a brief discussion, Watson comes to the conclusion Holmes has already reached:

"it is morally justifiable so long as our object is to take no articles save those which are used for an illegal purpose"And besides that, it's kind of fun:

"The high object of our mission, the consciousness that it was unselfish and chivalrous, the villainous character of our opponent, all added to the sporting interest of the endeavour."Well, that settles it.

So Holmes and Watson set off to break into Milverton's safe, but they have to duck into hiding when it turns out Milverton's still up, waiting for an appointment. And then this is where things turn either sublime or absurd, depending on your response to lines like "'It is I,' she said, 'the woman whose life you have ruined.'"

This, of course, is the problem all blackmailers face, though most don't have Holmes and Watson watching from behind a curtain when they're shot by past victims. Holmes figures justice is being served, so he hangs back until the woman's done, burns all the letters in Milverton's safe, and skips off back to Baker Street.

And when the police come around the next morning to get his opinion on recent events, he's not all that inclined to help out:

"'Dear me!' said Holmes. 'What was that?'He has some fun with the fact that he and Watson managed to leave behind a few traces of their presence, and makes it clear that he's not going to offer any material support to the investigation.

But there's one minor mystery left to clear up in the story, and Holmes spends the last paragraph taking care of that one: Among the portraits of "professional beauties" in a photographer's window, he locates the one of the woman at Milverton's house. Her identity, of course, is never revealed.

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

The trouble with bookmarking

Or, more precisely, the trouble with bookmarking stuff for the blog anywhere outside my blog links folder.

Remember last year's Anne of Green Gables extravaganza?

Turns out I'd found and saved an awesome-looking site, full of all those little details I love to point out. And then since I put it in the wrong folder, it never got worked into my chapter summaries.

So. Go check out http://www.lmm-anne.net/archives/. Enjoy.

Remember last year's Anne of Green Gables extravaganza?

Turns out I'd found and saved an awesome-looking site, full of all those little details I love to point out. And then since I put it in the wrong folder, it never got worked into my chapter summaries.

So. Go check out http://www.lmm-anne.net/archives/. Enjoy.

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Links again

Bookselling definitions in search of words -- brilliant.

Just because everyone else has already linked to the six-year-old judging books by their covers doesn't mean I'm going to skip it.

A case before the Supreme Court that hinges on the interpretation of the First Sale Doctrine.

New covers for Octavia E. Butler.

An elaborate and informative Amazon infographic.

Advice for beginning journalists.

Comments. Lots and lots of comments. On the DOJ antitrust settlement.

Just because everyone else has already linked to the six-year-old judging books by their covers doesn't mean I'm going to skip it.

A case before the Supreme Court that hinges on the interpretation of the First Sale Doctrine.

New covers for Octavia E. Butler.

An elaborate and informative Amazon infographic.

Advice for beginning journalists.

Comments. Lots and lots of comments. On the DOJ antitrust settlement.

Monday, July 23, 2012

Holmes Project: The Adventure of Silver Blaze

Let's start with the opening line.

Let's start with the opening line."'I am afraid, Watson, that I shall have to go,' said Holmes, as we sat down together to our breakfast one morning."On the one hand, we're getting a picture of a happy domestic scene here -- it's not hard to imagine Holmes and Watson calmly decapitating eggs and tucking in to the early edition of the paper. But "Silver Blaze" was published after the Holmes stories had started to take off, so anyone familiar with the characters was likely to understand that "I shall have to go" is the prelude to Holmes taking on a case.

But before getting into the details, Holmes and Watson get themselves onto a train for points southwest, and then Holmes calculates their speed by how quickly the train passes telegraph posts. And then we start into the framing for the backstory -- not the history of the case itself, yet, but the context in which Holmes is going to tell Watson all about it.

First, we have some theoretical context:

"It is one of those cases where the art of the reasoner should be used rather for the sifting of details than for the acquiring of fresh evidence."Which is, I suppose, a bit of a red herring, as the reasoner does in fact do some evidence-collecting later on.

And then a disclaimer:

"Because I made a blunder, my dear Watson -- which is, I am afraid, a more common occurrence than anyone would think who only knew me through your memoirs."Disclaimer with a side of "hey, we're fictional characters discussing the works in which we appear."

And finally we get the lead-in to the actual story:

"At least I have got a grip on the essential facts of the case. I shall enumerate them to you, for nothing clears up a case so much as stating it to another person, and I can hardly expect your co-operation if I do not show you the position from which we start."So we've got Holmes' own justification for a chunk of exposition that's necessary for the reader to know where things are going. A horse has gone missing, just before a race in which he's the favorite, and his trainer was found dead. Several people have been observed doing suspicious things, but none of them really make sense.

In the course of Holmes' monologue, one character is described as "doing a little quiet and genteel book-making in the sporting clubs of London." Isn't that an elegant way to depict a bookie?

There's another eye-catching line when it comes to describing the area they're headed to: "the little town of Tavistock, which lies, like the boss of a shield, in the middle of the huge circle of Dartmoor." (I consider this an appropriate point to insert a plug for Laurie R. King's The Moor. But as much as I love the Mary Russell books, I'm trying to stick with looking at Conan Doyle's writing here.)

Once Holmes and Watson arrive on the scene, we get one of the "Holmes is clearly up to something but we don't yet know what" moments:

"'Excuse me,' said he, turning to Colonel Ross, who had looked at him in some surprise. 'I was day-dreaming.' There was a gleam in his eyes and a suppressed excitement in his manner which convinced me, used as I was to his ways, that his hand was upon a clue, though I could not imagine where he had found it."There's a lot of concrete detail among the clues, some of which probably had more resonance with Conan Doyle's original audience than it does today. I can't say I've met anyone who smokes "long-cut Cavendish," for instance, and it takes a bit of calculating to translate "Twenty-two guineas is rather heavy for a single costume" into real money. (Decimalization may have eliminated some fun terms for standard amounts of money, but it does make the currency far easier to comprehend.)

Conan Doyle takes a moment here to throw in a lovely descriptive line that fits nicely into the story, even though it has nothing to do with the case itself:

"The sun was beginning to sink behind the stable of Mapleton, and the long, sloping plain in front of us was tinged with gold, deepening into rich, ruddy browns where the faded ferns and brambles caught the evening light. But the glories of the landscape were all wasted upon my companion, who was sunk in the deepest thought."Holmes is rather more focused on hypotheses, and Conan Doyle gives him another opportunity to explain how detection works:

"We imagined what might have happened, acted upon the supposition, and find ourselves justified."Oh, and also:

"I follow my own methods, and tell as much or as little as I choose. That is the advantage of being unofficial."It's also a good plan for a writer, no?

So even though Holmes has everything sorted out, Conan Doyle isn't going to let the reader know what he's thinking. And he gives Holmes a chance to show off, telling Colonel Ross that his missing horse will run in the upcoming race as expected, but the Colonel's just going to have to wait for it.

"'Yes, I have his assurance,' said the Colonel, with a shrug of his shoulders. 'I should prefer to have the horse.'"And then, as Holmes is about to take his leave without providing any answers, Conan Doyle gives us one of his most famous passages:

"'Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?'And... scene. Always leave your audience wanting more.

'To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.'

'The dog did nothing in the night-time.'

'That was the curious incident,' remarked Sherlock Holmes."

We finally get the explanation four days later, when Holmes and Watson go to see the missing horse run its race. And it does run, even though it looks completely different from the last time it was seen.

And Conan Doyle allows Holmes, in a very arch way, to draw out the resolution of the story even more:

"But there goes the bell, and as I stand to win a little on this next race, I shall defer a lengthy explanation until a more fitting time."Which he does, very neatly, accounting for lame sheep, dress purchases, and an illicit dye job, as well as the murderer -- who, he explains, was merely acting in self-defense.

(Full text)

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

The Sherlock Holmes project

In Maps & Legends, Michael Chabon has an essay about Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories (and their universe, and the world of Sherlockians and fanfic and such that they spawned, which is the point of the essay, but not where I'm going here.

One of the things Chabon discusses as he builds to his point is level of Conan Doyle's writing in the stories -- "so much higher than it ever needed to be," he calls it. And it's not just good writing, it's writing that plays with form and narrative and metafiction. (In other words, the way Holmes and Watson know that they're characters within stories that the public is devouring, even as they go about their fictional lives. Let's have this be the last time I get all jargony here.)

So now that I've spent time focusing on Jane Eyre, Anne of Green Gables, The Witch of Blackbird Pond, and the men of Madeleine L'Engle, I think the Holmes stories will be my next big project. (And I do mean big. There are 56 of them, plus the novellas. We'll take it in small doses, shall we?)

First up: The Adventure of the Silver Blaze.

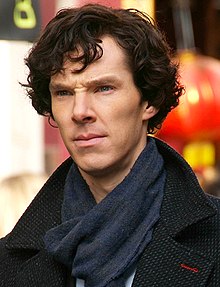

(Post pics: a passing resemblance, don't you think?)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)