"One British scholar who studied the Venuses in his youth never noticed any clothing because, he recalled, he 'never got past the breasts.'"

You know how women sometimes complain about men speaking to their breasts rather than their faces? That's nothing compared to what the prehistoric European figurines (most of them called Venus of Something) have put up with.

It's something I've been especially cognizant of since reading

The Invisible Sex by J.M. Adovasio, Olga Soffer, and Jake Page. And it's why this

Reuters article, filed under "Oddly Enough," set me off, starting with the title.

"Sexy Venus"? This is not a prehistoric pinup girl. (Which, I found out only after typing that, is

exactly the term Nature uses, at least on its

website, to describe the figure. I thought Reuters might have been dumbing down, but it seems the blame lies elsewhere.)

The

Nature letter and accompanying

commentary discuss a recently discovered figurine that bears some resemblance to the known ones, like the

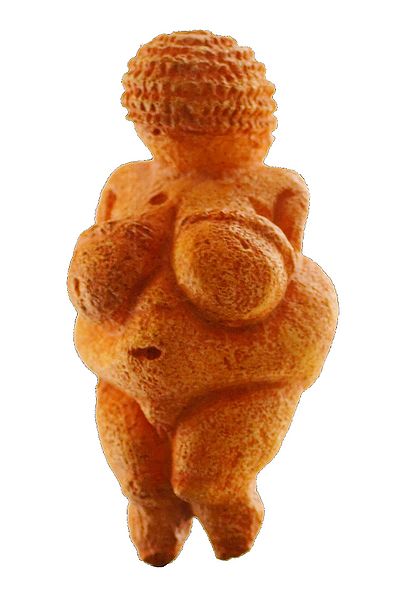

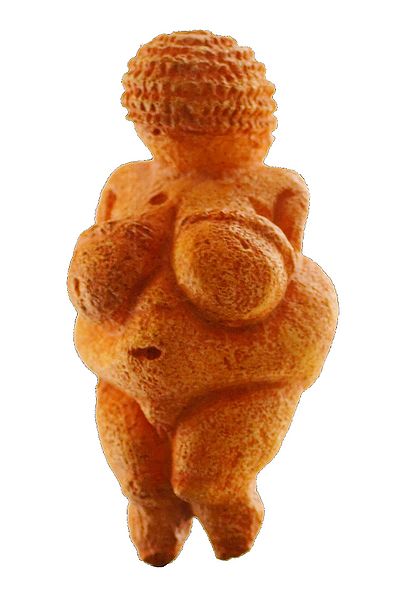

Venus of Willendorf,

Venus of Brassempouy, and

Venus of Lespugue, but is 5,000 years older than any known figurine of this type.

So it's huge - these figurines are thought to represent, among other things, the concept of gender as distinct from sex, which was a big step in the development of human consciousness.

As in, it happened earlier than we thought.

Those of us who bother with thought, at least, and don't get stuck on the idea of what

The Invisible Sex calls "paleoporn."

Adovasio and Soffer took their eyes off the breasts for a while and focused on what appear to be braids. And they found that "a close inspection of the braids of the Venus of Willendorf showed that her 'hair' was, on the contrary, a woven hat, a radially hand-woven item of apparel that was probably begun from a knotted center in the manner of certain coiled baskets made today by Hopi, Apache, and other American Indian tribes."

Which is significant, because based on the amount of detail in the hat, "the carver had to have spent more time on just the hat than on the rest of the entire figurine." Seems like the important part, no?

That's not to say there's no sexual aspect: "There is simply no denying that the sculptors of these figurines went to a great deal of trouble to show off the sexual and secondary sexual features of the female human, even to the point of leaving the rest of the figure - face, feet, arms, and so forth - either abstract or absent altogether."

But they - and there's plenty of speculation about the identities of the carvers - don't seem to have put the figures in the plain brown wrapper that Reuters,

Nature, and the latest researchers are reaching for.

(All quotes from the ARC version of

The Invisible Sex, which is a plausible takedown of standard man-the-mighty-hunter versions of prehistory and other ways to interpret archaeological evidence. There's a reason the ARC still has a home on my shelves.)